Professor Teaches A World Of Music

Professor Teaches a world of music

U-M's Standifer shows S. Africans a language they can share

By LIZ COBBS

When James Standifer was in South Africa © in the past two summers, participants in his workshops got a taste of what a new South Africa could be like.

Standifer showed educators and students how various ethnic groups, now segregated by apartheid, can be brought together — through the universal experience of music.

“They were aware that South Africa was replete with multiculturalism, and it was clear to them that they had not taken advantage of it,” he says. “I tried to show them the differences in their cultures but also the similarities of their cultures. Hopefully, the result will be mutual understanding and respect among groups, individuals and cultures.”

A music education professor and multicultural education specialist at the University of Michigan, Standifer was awarded a distinguished visiting professorship at the University of Natal at Durban in 1989 to teach multicultural music education.

This past summer, Standifer was invited to return to South Africa and was awarded an ac-ademic specialist grant by the U.S. Informa-tion Agency to teach U.S. trends in multicultural education and multicultural music education at schools across South Africa.

While there, he lectured and conducted workshops at elementary and secondary schools, teacher-training colleges, and universities attended by whites, blacks, Indians and those of mixed descent.

“They all wanted practical techniques and a philosophical basis for getting diverse groups together,” says Standifer, 54, who has also re4searched Afro-American, Korean and Chinese music. “The musical cultures of South Africa are diverse and substantial, but they remain largely untapped as sources of material for school and college use.”

During his workshops at segregated schools and colleges, he demonstrated the musical traditions of other cultures in South Africa and the United States. He encouraged people from different ethnic groups to come together and share each other's music, but found that it remains difficult because of government-imposed racial segregation.

At universities in Cape Town and Natal, he was able to offer workshops where people of different ethnic backgrounds could attend and celebrate each other’s musical styles.

Unlike America where different types of music — classical, Latin, jazz, pop, gospel — reflect the diversity of cultures in the country, music in the South African school system reflects that of Western Europe and not of the diverse South African cultures, he says.

“Black South Africa is an enormously rich singing society, and a cappella singing, in particular, is the norm among black South Africa,” he explains. “However, Pretoria sees little need to capitalize on this rich resource and when it does, it forces teachers to have students put their song in a musical system deemed compatible with the musical traditions of white schools.”

A “central committee” in Pretoria, the capital of the Republic of South Africa, develops the music education system for white, black, colored and Indian schools, he says, without input from teachers, parents or administrators, leaving them “frustrated and angry.”

“The government is committed to keeping separate developments of each group without consideration of the unavailability of teachers and the inequities of funding,” he says. “Since blacks make up, the largest population in South African schools and are the most economically disadvantaged, they are obviously the ones who are hurt the most.”

Promoting multiculturalism in music education in various societies is just one of the many goals of Standifer, whose background is as diverse as music itself.

Before coming to the University of Michigan in 1971, Standifer taught at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio; Temple University in Philadelphia; and in the Cleveland Public Schools.

A prolific writer, Standifer has had numerous works published and worked as a music consultant nationally and internationally. He was senior adviser and research associate for “From Jumpstreet: The Story of Black Music,” a nationally televised Public Broadcasting System series in 1980.

In 1974, he was named director of the university’s Afro-American Music Collection and donated the N.C. Standifer Video Collection to the U-M in 1980. The Standifer Collection, named after his father who died in 1985, contains more than 100 videotaped interviews of legendary black musicians such as William Grant Still, Mary Lou Williams, Eubie Blake, Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Charles, Lena Horne, Tommy Dorsey, B.B. King and Count Basie.

Standifer is currently involved in a research project on dances in wedding and puberty rites of Zulu girls as well as "isicathamiya" - dances of black men in urban South Africa — which were made popular in the U.S. by Paul Simon’s support of the Ladysmith Black Mambazo group, which appeared in Ann Arbor two years ago. The research is funded by the School of Music and the Office of the Vice President for Research at the U-M.

While his myriad activities keep him very active, helping people understand different cultures remains the top objective for him.

“Misunderstanding and ignorance are likely to breed fear, and fear breeds prejudice,” he explains. “Prejudices are apt to remain. However, in the new South Africa it is inevitable that the diverse cultures there will have close interaction with each other.

“At such time, mutual respect and sensitivity toward each other will be the basic ingredient necessary to move the society successfully into the 21st century. And, the wonderful thing, in my view, is music, art, and culture will have an important role in this phenomenon."

ANN ARBOR NEWS PHOTO . ROBERT CHASE

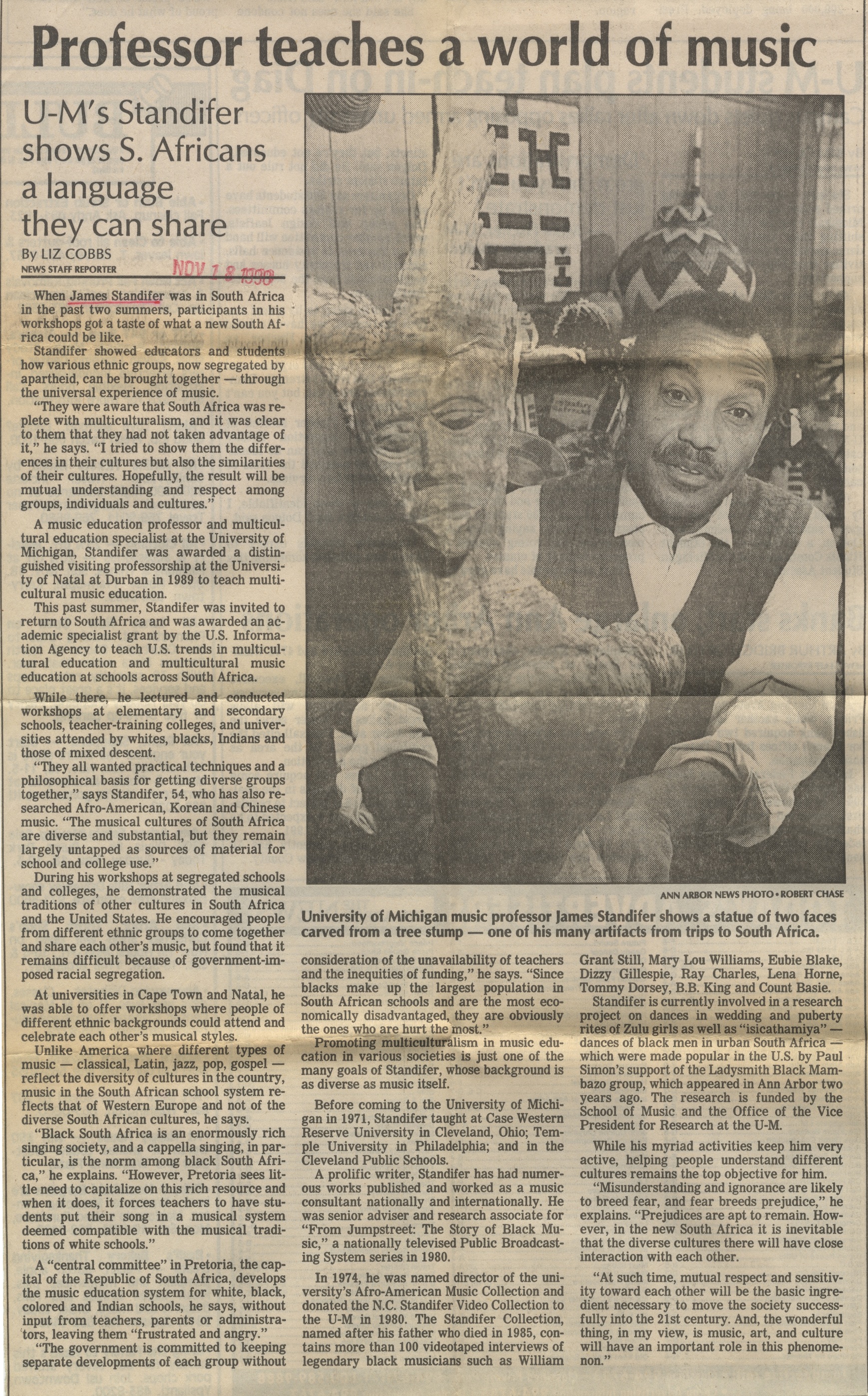

University of Michigan music professor James Standifer shows a statue of two faces carved from a tree stump — one of his many artifacts from trips to South Africa.

Article

Subjects

Liz Cobbs

Black American Community

Black History

Eva Jessye Afro-American Music Collection

University of Michigan - Faculty & Staff

University of Michigan School of Music

N. C. Standifer Video File

Ladysmith Black Mambazo

University of Michigan - Office of the Vice-President for Research

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

James D. Standifer

Robert Chase